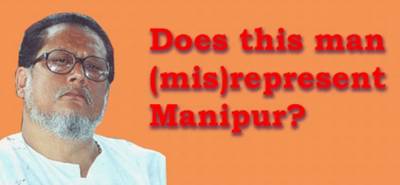

Where are Ratan Thiyam’s roots?

I have never seen a single play of Ratan Thiyam, but deep in my heart, I respect him as any Manipuri would (and should) with a sense of awe and veneration. He is a cultural icon, one of the truest sons of the soil. Never has a Manipuri reached such heights of excellence and fame in his chosen field - be it at national level or international stage. A chance visit to his webpage has further reinforced my estimation of him as a genius. The countless number of awards and prizes and other recognitions that his theatre has earned over nearly three decades is mind boggling and colossally impressive. It makes me wonder: well, will we ever see another Manipuri who will be even a tad close to his stature and talent in any specialised discipline. And at the risk of sounding morbidly immature, it is tempting to ask - after Mr. Thiyam, who will inherit his craft and conduct it forward as nearly professionally as this guru with extraordinary results.

Ratan Thiyam is one of the directors that came into limelight as a director of "theatre of roots", a movement pioneered by other giants of Indian theatre like B. V. Karanth, Habib Tanvir, Bansi Kaul, Vijay Tendulkar, etc. in the 70s. These directors exploited traditional folktales and contemporised them in their theatrical narrative and execution. To Mr. Thiyam especially, this genre must have presented an added incentive as it enabled him to connect to his roots, an opportunity that any Manipuri would have snatched in the land of the mayangs. Indeed, he became the poster boy of the theatre of roots, dwarfing all the earlier trailblazers.

But the question remains: does his theatre really represent his roots, and for that matter the Manipuri society, its ethos and culture? If you take a cursory look at his plays, the answer would be almost negative: finding an unalloyed true Manipuri influence in his theatre will be like looking for a needle in the haystack.

"Uttar-Priyadarshi," the jewel of his ouevre - that catapulted Mr. Thiyam to the galaxy of world's greatest directors - is as Manipuri (or unManipuri) as the samosa. Why is the title of most of his plays in Hindi? His latest offering is even named in Hindi words that seem like Greek to some of us - 'Ritusamharam'. Never mind the theme that, as far as he claims, is 'rooted' in typical Manipuri season of spring when the Nature opens forth her bounty. So far, so good. But then, call it his pandering to the Indian audience or hunger for more of thier patronage, he seems to have lost his Manipuri soul when he gratuitously made 'Holi-playing' the focusing point of the play. There is nothing wrong in portraying Holi, while ignoring yaoshang; after all he has the artistic license to do whatever he like - make his work overtly sub-continental or Manipuri. In this case, his choice was undeniably Indian in theme, with heavy dose of Hinduism element thrown in. Which is well within his rights, except for one problem that he made his name solely on the notion that he represented the "theatre of roots" movement. Will someone point out where does his roots lie actually - in Kurushetra or Manipur?

I may be blamed as xenophobic, nit-picking and even ungrateful, but let me assure you I have company, and they are not even Manipuri. At a screening of a documentary on Ratan Thiyam, "Some roots grow upwards," recently in New Delhi, a young filmmaker from the audience got up to ask the director of the documentary, Kavita Joshi, if Mr. Thiyam's works were aimed at projecting a "pan Indian Hinduism" consciousness. I was astounded, not least because those were the words which were on my tongue tips, but because an outsider could also notice that hallmark of Ratan Thiyam's theatre.

Ms. Kavita presently summoned her composure and said something to the effect that Ratan Thiyam was merely using known epics as a vehicle to promote his agenda of peace and harmony, and that it was a technique that directors of all hues and colours elsewhere resorted to. Later, in a telephonic interview, she defended Ratan Thiyam, saying he could not be faulted as his works "mirror the Manipuri society" that had many layers underneath. Clearly, she believed that all Manipuris were Hindus, and pointed out that only two members in the cast crew of Chorus Repertory Theatre had Meitei names, for instance.

When Mr. Thiyam is not drawing upon Hinduism's crutches, he borrows from some other religions alien to Manipuris. After seeing his Uttar-priyadarshi at Washington, Tehreema Mitha, an Indian crtic, felt that "it presents a very Buddhist attitude towards violence," and that spawned a "confusion, since India is perceived as basically Hindu".

Mr. Ratan Thiyam should do a soul searching and change the direction of his works to make it more representative of the Manipuri society, her culture, her history, her folktales and her identity. Foisting Manipuri ideological theme on archetypal Hindu epics may earn him brownie points in the initial stage of his career - and we can understand it - but now he is 'big' enough to chart his own course and create plays that is truly Manipuri from head to tails. Instead of trying to find strained (and strange) parallels with Manipur's social and political realities in some obscure Vedic traditions, he should look for gems in his own backyard. After straying away for more than two decades in wilderness in search of his roots, atop ivory's tower, Mr. Thiyam should return to his fertile soil that gave birth to him. If he must take a leaf from his great contemporary, Tadashi Suzuki, so be it, but come back home. The rewards would be more satisfying than any foreign recognition.

<< Home